Difference between revisions of "Digital technologies/3D printing/3D modeling- Beginner"

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

#Position: Position refers to the distance separating a feature and an (ideally) meaningful reference (i.e.: the distance between a hole and the side of a part, or between two holes). Thankfully, flaws pertaining to position are rare on a properly tuned printer, as the printer does not have any information about existing references other than the build plate. If tuned properly, the printer will always print a feature at a position (X,Y,Z) distance relative to another feature, because that is what the gCode will tell it to do. You can imagine, however, that if the part is warped, the 'build plate reference' is no longer valid, and such, warped parts almost always have features out of position ''<u>unless the meaningful reference (interfacing feature) used in the design is not the build plate</u>''. However, since the build plate reference is such an important one to define the Z position of features (for the printer, that is), making your meaningful reference something other than the build plate does not always guarantee you good positional tolerance independent of warping. | #Position: Position refers to the distance separating a feature and an (ideally) meaningful reference (i.e.: the distance between a hole and the side of a part, or between two holes). Thankfully, flaws pertaining to position are rare on a properly tuned printer, as the printer does not have any information about existing references other than the build plate. If tuned properly, the printer will always print a feature at a position (X,Y,Z) distance relative to another feature, because that is what the gCode will tell it to do. You can imagine, however, that if the part is warped, the 'build plate reference' is no longer valid, and such, warped parts almost always have features out of position ''<u>unless the meaningful reference (interfacing feature) used in the design is not the build plate</u>''. However, since the build plate reference is such an important one to define the Z position of features (for the printer, that is), making your meaningful reference something other than the build plate does not always guarantee you good positional tolerance independent of warping. | ||

#Surface: The surface finish of a part is a rather complex subject. In 3D printing, and for typical applications of 3D printed parts, it mostly refers to the mean (statistical) difference between the height of cusps and valleys on a part and their deviation from that mean, at a macroscopic level. The most important consideration is that when 3D printing, most surface finishes are quite rough (deviate significantly from the mean), and thus are sanded down considerably to knock out the cusps left by the printer. This post processing can negatively affect the form of the final part. | #Surface: The surface finish of a part is a rather complex subject. In 3D printing, and for typical applications of 3D printed parts, it mostly refers to the mean (statistical) difference between the height of cusps and valleys on a part and their deviation from that mean, at a macroscopic level. The most important consideration is that when 3D printing, most surface finishes are quite rough (deviate significantly from the mean), and thus are sanded down considerably to knock out the cusps left by the printer. This post processing can negatively affect the form of the final part. | ||

| + | [[File:Design for 3D Printing Generatively Designed Bracket.jpg|alt=3D printed bracket|thumb|A metal 3D printed generatively designed bracket (computer generated from load data, using Finite Element Analysis), likely replacing a multitude of other parts that would have been manufactured using traditional manufacturing methods which would lead to a heavier and more expensive bracket.<ref>CarrusHome (2021). GM Explores 3D printing, generative design for next gen parts. Consulted on 05/05/2022 at https://www.carrushome.com/en/gm-explores-3d-printing-generative-design-for-next-gen-parts/</ref>|450x450px]] | ||

Note that ''<u>a proper mechanical fit between components demands a good tolerance on form, feature position, and surface finish</u>'', such that it is typically impossible to obtain a proper fit when 3D printing, and that if you are considering the 3D printing of critically interfacing components, 3D printing should not be used unless post processing <u>''is built into the design''</u>. For mechanical designs, you will notice that a main application is brackets. This is because brackets only need good positional tolerance on holes and mating faces, which 3D printing can almost always provide (the tolerance on form for holes is not that important since they are typically clearance holes). However, since some brackets are easily laser cut, 3D printing brackets is only done under certain specific conditions. It certainly has shown its commercial use in cost cutting by replacing intricate multi-part assemblies by ''generatively designed'' (we'll say computer generated for now) parts, as shown in the picture below. | Note that ''<u>a proper mechanical fit between components demands a good tolerance on form, feature position, and surface finish</u>'', such that it is typically impossible to obtain a proper fit when 3D printing, and that if you are considering the 3D printing of critically interfacing components, 3D printing should not be used unless post processing <u>''is built into the design''</u>. For mechanical designs, you will notice that a main application is brackets. This is because brackets only need good positional tolerance on holes and mating faces, which 3D printing can almost always provide (the tolerance on form for holes is not that important since they are typically clearance holes). However, since some brackets are easily laser cut, 3D printing brackets is only done under certain specific conditions. It certainly has shown its commercial use in cost cutting by replacing intricate multi-part assemblies by ''generatively designed'' (we'll say computer generated for now) parts, as shown in the picture below. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Supports=== | ===Supports=== | ||

| + | [[File:Poor-surface-above-supports.jpg|alt=Poor surface finish over supports|thumb|Picture showing the surface likely obtained over supports. As can be seen, the finish is extremely coarse.]] | ||

As explained in the 3D printing page, supports are sometimes required to support overhanging sections of a print. Due to the downsides of supports discussed below, it is typically better to avoid supports altogether when designing for 3D printing. | As explained in the 3D printing page, supports are sometimes required to support overhanging sections of a print. Due to the downsides of supports discussed below, it is typically better to avoid supports altogether when designing for 3D printing. | ||

Revision as of 13:50, 6 May 2022

Tinkercad is an easy software that allows you to design 3D designs. It is easy to learn and simple to use. We strongly suggest you use this if this is your first time designing in 3D. To begin with, go to tinkercad.com and create an account. We recommend you create an Autodesk account. It's free and if you are a student, you get to have access to a bunch other Autodesk software for free!

TinkerCAD Layout

Splash Page (Designs & Projects)

The TinkerCAD splash page is very simple. On the left, you may switch design categories. This is necessary because TinkerCAD allows design of electronics circuitry and code as well as 3D modeling! For this wiki page, the relevant mode is 3D Design. On the centre of your page, you will find all your designs. It is recommended that you do not forget altogether about the navigation on the left, since chances are that you will want to create a project at some point, that will include all three design categories, for which we recommend you create a project in TinkerCAD, which can hold all design categories. This will help with keeping your workspace organised. The following buttons are useful

- Tinkercad logo: Clicking on the Tinkercad logo with bring you back to the splash page

- LEARN: The LEARN is where you can find tutorials to help you navigate the software a little easier. There are also lessons walking you through basic projects to inspire different ideas and to practice with the software.

- GALLERY: The GALLERY is where you can see projects that other people have made visible to the public, you can copy and modify those designs or inspire yourself from them.

- Create a new design: To create a new design in Tinkercad, sign in and it will lead you to the desktop. Select the Create new design button and this will bring you to a blank workspace.

If you wish to modify a 3D model, click on the model on the main section, and then click 'Tinker this' to access the CAD Modeling page.

CAD Modeling

The design page has quite a few sections and buttons, but it all remains quite straightforward. Refer to the following image for a list of buttons. For some of the buttons, the function is self-explanatory. If you are unsure what a button does, it is likely that the function is explained in the rest of the 3D modeling beginner content.

Create a New Design

When you click “Create a new design" in the splash page, you are brought to a new window with a blue, gridded, base workplane (as illustrated in the section above). Think of the base workplane as a floor or the base of the 3D printer. You want to make sure that the part you are building is sitting on the this surface. This is where you will do your designing. There are several tools which you can use to help you design.

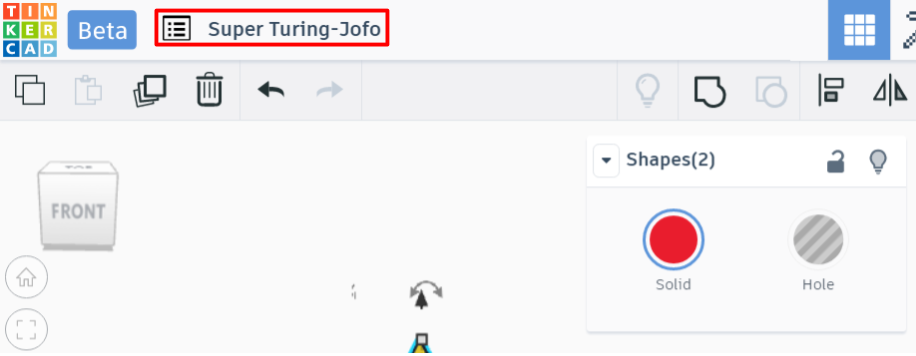

- Name of your design: To change the name of your design, click on the automatically generated name that is in the top left corner. This is useful to be able to find the design later and know what it is.

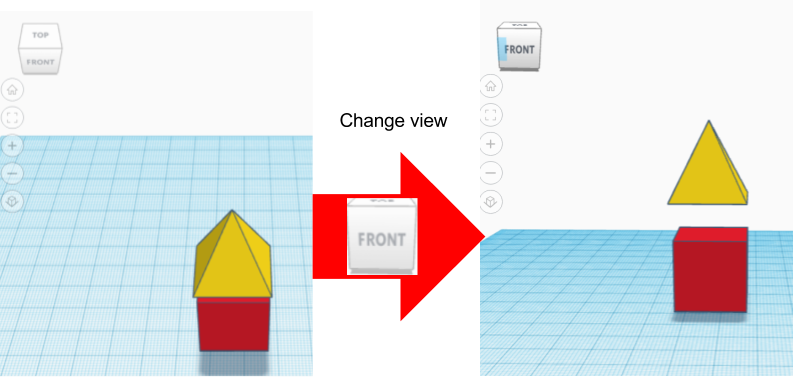

- View square: Drag around the square to change the viewing angle.

- View buttons: Bring the viewing angle back to home, change the zoom, switch to orthogonal view

- Show all: This will show any hidden shapes. While designing, you can choose to hide a shape. This is sometimes helpful if you want to see a piece that is under another.

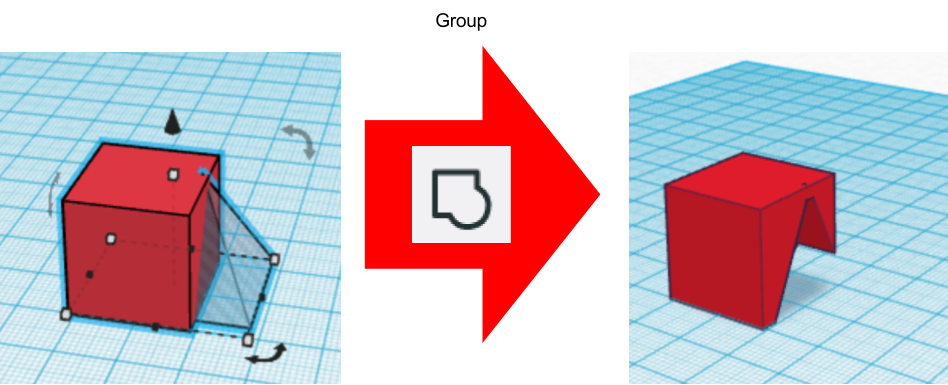

- Group: Take several shapes and turn them into one shape

- Ungroup: Take a shape that is composed of several pieces, and separate them back into individual pieces.

- Align: Align several pieces

- Mirror: Mirror a component

- Import: You can also import shapes that have already been created using the Import button. You can add both 2D and 3D shapes. The file type for 2D shapes needs to be “.svg”, and the file type for 3D shapes is “.stl” or “.obj”

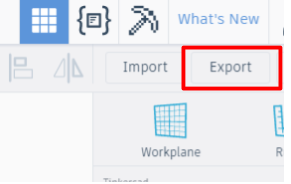

- Export: Download the selected object or everything on the build plate. Download it as an .stl for 3D printing and a .svg for laser cutting.

Using TinkerCAD

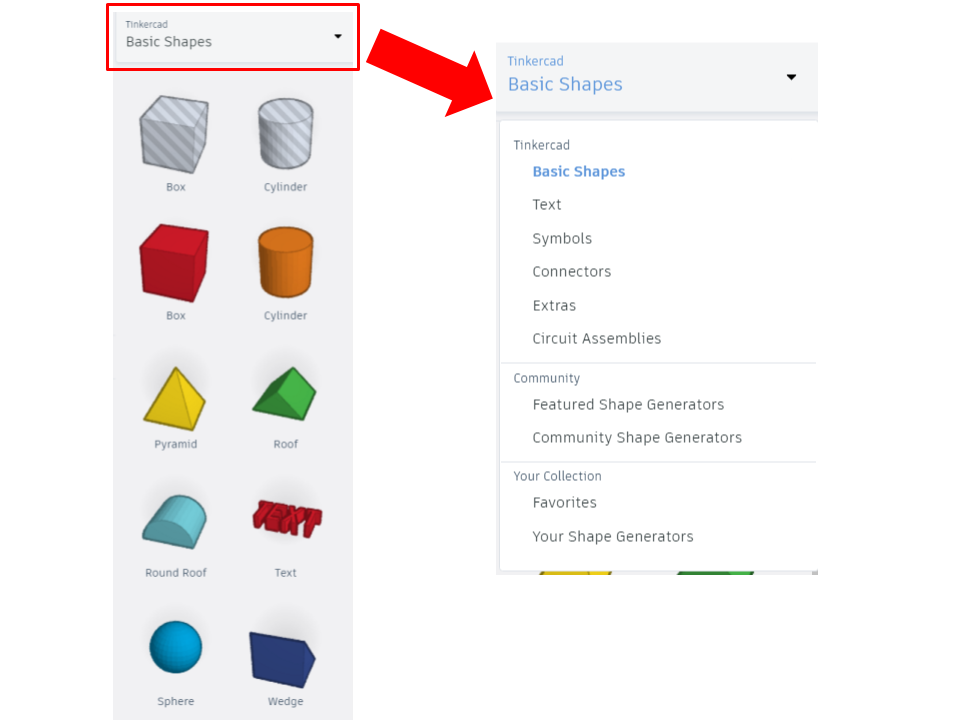

On the right hand side there are a series of different shapes that you can place on the your workplane (shape browser). These are your building blocks. If you click on building Basic Shapes you can select different types of shapes (or blocks).

There are shapes that are registered as Holes by default. These are hatched gray and white on the shape browser. If you move them to the workplane, they will appear translucent. As you will learn, this is not very useful because any shape can be turned into a hole. For example, if you found model you liked on Tinkercad and you wanted to add a new hole.

Once you have your shape you can change the size with:

- Black cube: Change one dimension

- White cube: Change two dimensions (unless it is the shape's height)

- Curved black arrows: Rotate shape in that plane

- Black cone: Raise or lower shape

If you are putting a piece on top of another, make sure the piece is not floating. Every piece should be touching another one or be on the platform.

When you have a shape selected, the Shape window will open on the top right part of your workspace. This tool lets you choose if this shape is solid (coloured in the workspace) or a hole (hashed and translucent in the workspace). If you want your shape to be a hole, select the hole button and the shape should become translucent. Mind you, it will not actually take into affect until you group those two objects. The group button, found on the top right hand side of your workspace (on the top ribbon), will only be available when there is more than one shape selected. You also want to group all your shapes before downloading (exporting) a model for 3D printing (unless you are working with 2 extruder heads and you want shapes to print independently from one-another).

To change the name of your design, click on the automatically generated name that is in the top left corner. This is useful to be able to find the design later and know what it is. It is good practice to aim for a relevant name.

Other Tools in TinkerCAD

Other useful tools can be found above the Tinkercad shapes menus.

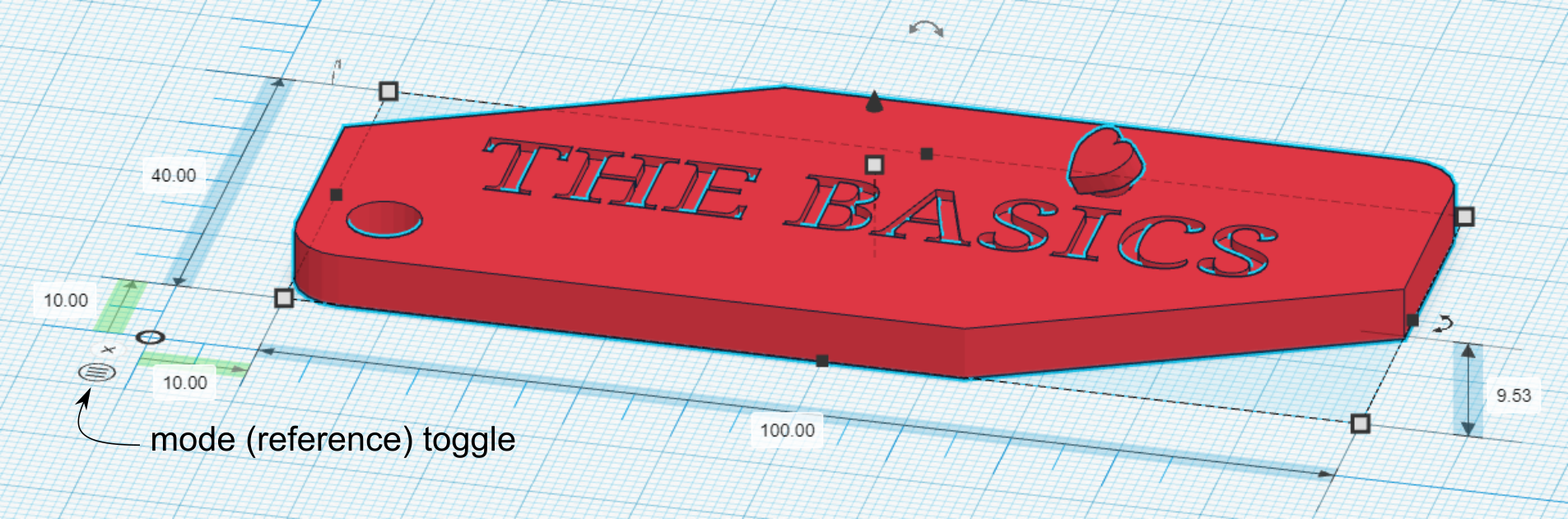

| Ruler (R) allows for you to easily change the dimensions of a shape. Just place it anywhere on the workplane and dimensions from the ruler origin to the part origin as well as the part's major dimensions will appear. Just click on any of the dimensions and you can change their value. Highlighted in blue are the major dimensions, in green are the offsets between the shape's origin and that of the ruler. The ruler tool also has a mode where changing the dimensions of the shapes will happen symmetrically from the shape's midplanes. Simply click on the circled three lines (bottom left of the ruler origin) to toggle between modes. Toggling will change the reference of the ruler to the centre of the shape. | |

Next to the group button, there is another set of useful tools, Align (L) and Flip (M).

Printing your Design

When you are done, and you want to print your new design, click Export at the top right corner.

A new window will appear. If you want to 3D print, choose which shapes you want to print (everything or only some selected shapes) and select the format .STL. If you want to laser cut a projection of the shape, select the format .SVG.

For the actual 3D printing or your part, refer to the steps found in the 3D printing pages.

Importing Models to TinkerCAD

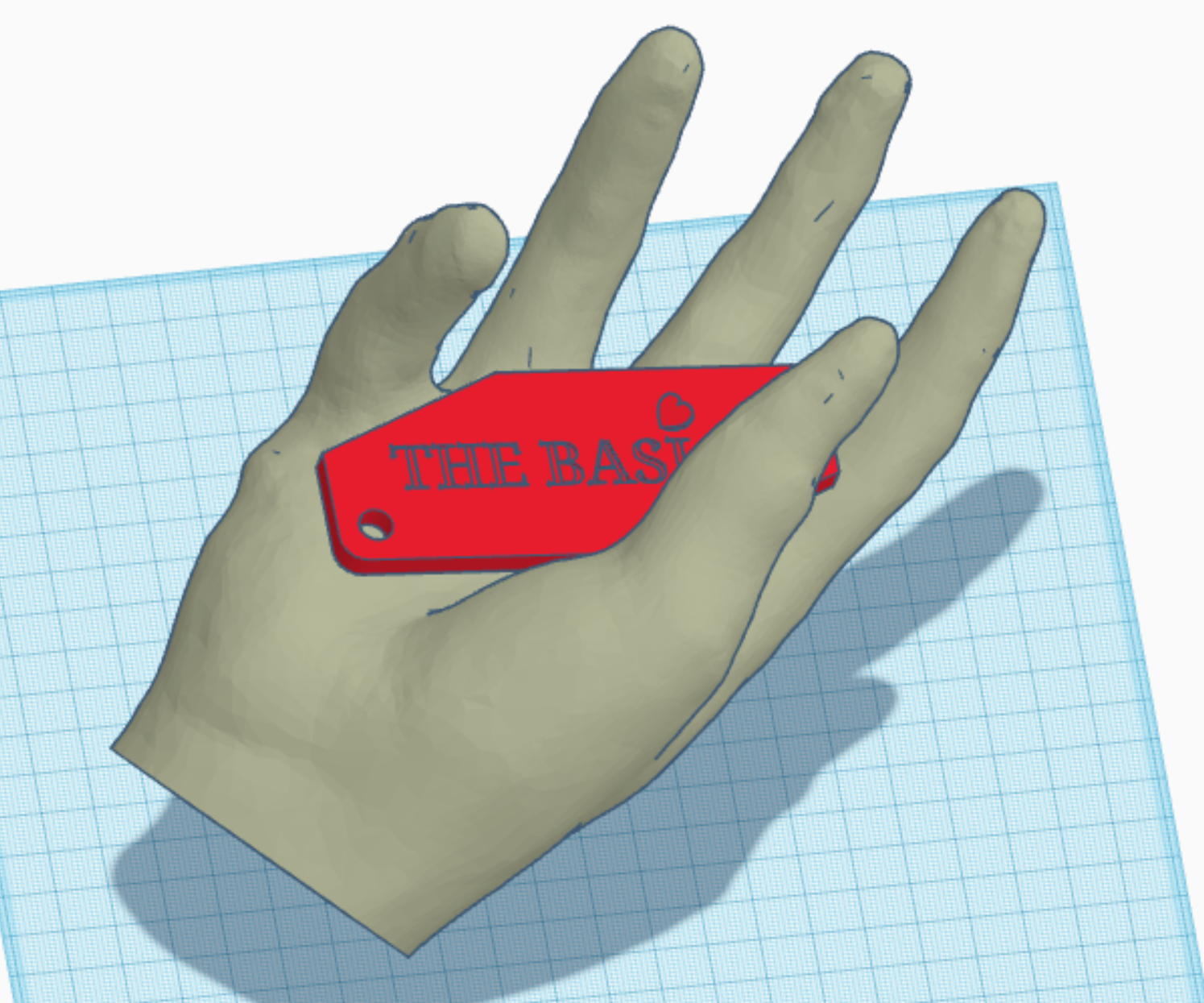

TinkerCAD can be a powerful tool for repairing or editing polygonal models (defined by triangles). Therefore, it is considered fundamental to CAD modeling in TinkerCAD to know how to import a model. You may import polygonal files (STL, OBJ, etc.) to TinkerCAD for modifications, repairs, etc. For example, if one wanted to add a label they designed to a model of a hand, this could be done in TinkerCAD. A hand is however hard to model, but there are lots of them on community CAD libraries, such as Thingiverse or GrabCAD. All that needs to be done, is for the model to be downloaded, and imported into TinkerCAD using the Import button. Once the model is imported, it will appear on the workplane. All the controls relating to shape modifications apply to the imported model! Here's an example of a composite model with the Thingiverse hand and the label from the beginner level proficiency projects example tag:

Design for 3D Printing

It is very important, while designing, to be aware of the limitations of the manufacturing method which will be used to make your design reality. Since this article focuses on 3D modeling for 3D printing, this section will only focus on those considerations relating to 3D printing. If you are unsure how 3D printing works, it is imperative that you read through the Beginner 3D Printing page on this wiki for you to understand the concepts and considerations discussed below. If your design is to be used in (electro-)mechanical assemblies in which there are interfacing components, is also important that you understand three basic tolerancing concepts and to keep them in the back of your mind when modeling or more generally designing these assemblies. If you will not be designing mechanical and electromechanical assemblies, you can skip to the next subsection.

- Form: The form of a part refers to the overall dimensions and the shape of the exterior surfaces of a component. Think of a flaw referring to form as a print that ended up not matching the base geometry that was used to create it in CAD due to adverse physical variables during the printing process. Examples follow:

- A sphere may end up slightly oval once printed due to improper cooling, etc.;

- A pillar might end up tilted to one side due to improper belt tension between the belt axes, etc.;

- A pin feature might end up too large to fit its mating hole due to the printer outputting too much material when producing the outer walls of the feature (the inverse can also be true).

- Position: Position refers to the distance separating a feature and an (ideally) meaningful reference (i.e.: the distance between a hole and the side of a part, or between two holes). Thankfully, flaws pertaining to position are rare on a properly tuned printer, as the printer does not have any information about existing references other than the build plate. If tuned properly, the printer will always print a feature at a position (X,Y,Z) distance relative to another feature, because that is what the gCode will tell it to do. You can imagine, however, that if the part is warped, the 'build plate reference' is no longer valid, and such, warped parts almost always have features out of position unless the meaningful reference (interfacing feature) used in the design is not the build plate. However, since the build plate reference is such an important one to define the Z position of features (for the printer, that is), making your meaningful reference something other than the build plate does not always guarantee you good positional tolerance independent of warping.

- Surface: The surface finish of a part is a rather complex subject. In 3D printing, and for typical applications of 3D printed parts, it mostly refers to the mean (statistical) difference between the height of cusps and valleys on a part and their deviation from that mean, at a macroscopic level. The most important consideration is that when 3D printing, most surface finishes are quite rough (deviate significantly from the mean), and thus are sanded down considerably to knock out the cusps left by the printer. This post processing can negatively affect the form of the final part.

Note that a proper mechanical fit between components demands a good tolerance on form, feature position, and surface finish, such that it is typically impossible to obtain a proper fit when 3D printing, and that if you are considering the 3D printing of critically interfacing components, 3D printing should not be used unless post processing is built into the design. For mechanical designs, you will notice that a main application is brackets. This is because brackets only need good positional tolerance on holes and mating faces, which 3D printing can almost always provide (the tolerance on form for holes is not that important since they are typically clearance holes). However, since some brackets are easily laser cut, 3D printing brackets is only done under certain specific conditions. It certainly has shown its commercial use in cost cutting by replacing intricate multi-part assemblies by generatively designed (we'll say computer generated for now) parts, as shown in the picture below.

Supports

As explained in the 3D printing page, supports are sometimes required to support overhanging sections of a print. Due to the downsides of supports discussed below, it is typically better to avoid supports altogether when designing for 3D printing.

Form and surface roughness

Supports will also require post processing such as removal and sanding (if a nice smooth finish is desired). When designing for mechanical assemblies, it is important to keep in mind that supported sections might sometimes sag slightly, affecting the form of the surface being printed. Therefore, when designing (modeling), make sure that interfacing geometries (those for which the correctness of the shape, or form, is critical as it is interfacing with other parts) are not overhanging.

Hard to access supports

Support removal should always be an important consideration whenever using them. Unless of course you are fine leaving your supports in your print (in which case you might as well enclose that volume and have it be an infilled volume), you will have to remove your supports at some point, and such, you should have them be easily accessible with at the very least some snub nose pliers. While soluble supports are an option, they are practically never used in our Makerspace for prints unless the surface finish and form of the print over a support is critical. While soluble supports are cool and all, most designs can avoid containing supports that are hard or impossible to reach.

Build plate adhesion

When printing, adhesion is one of the main considerations. Make sure your design contains an adequate flat section that, if used as a base for the print, will not lead to excessive overhangs. The Thingiverse hand is a bad example the way it is positioned in Importing Models section of this article, but the way the flat section of the wrist is designed, and considering the position of the fingers not significantly overhanging (perhaps the pinkie is slightly overhanging), placed on the its flat wrist section, this hand model is expected to print properly without the use of extra adhesion features, or even supports!

Large prints

Extremely large prints cannot fit your regular build plate (or build volume). Yes, the makerspace does own 3D printers with larger build volumes, but those using them are typically charged for machine time. Instead, it can be extremely easy to split larger prints into smaller sections, and to then adhere these components together once they are all printed. The result might even look better, as sectioned parts can be oriented on the build plate to reduce the use of supports or improve adhesion.

References

- ↑ John-010 (2012). iPhone Hand. Thingiverse, accessed 2021-08-17 at https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:31331

- ↑ CarrusHome (2021). GM Explores 3D printing, generative design for next gen parts. Consulted on 05/05/2022 at https://www.carrushome.com/en/gm-explores-3d-printing-generative-design-for-next-gen-parts/